Core Concepts

Table of Contents

- Repositories: Distributed Version Control System

- File Areas: Worktree, Index, and Repository

- Refs and Objects: HEAD, Branch, Commit, Tree, and Blob

- Next

Repositories: Distributed Version Control System

Commands like push and pull (which is really a shortcut to fetch, then merge) copy files between local and remote repositories.

Remotes, like the one in Azure DevOps, are not special. Internally they are exactly like your local clone. You can git init --bare a new repository on a shared drive, add it as a remote using the file path and push to it. You could even push directly into your coworker’s local remote if you had file access.

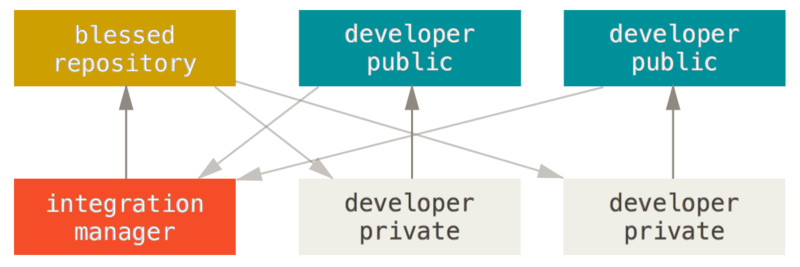

You can build any kind of file sharing workflow. Git is just a tool to copy files. Often centralized workflow is sufficient, but many projects like the Linux kernel use other workflows. The image below is the “Integration Manager” workflow described in the article “Distributed Workflows”. Each box is a different repository and the arrows show the direction files move. The developers work in their local private repos and push to their public repos. The manager pulls from the public dev repos into their private integration repo. The manager pushes completed integrations to the public “blessed repository”. Finally the other developers pull coworkers’ changes into their private repos to begin new work.

Git has no file locks. Instead, two changes to the same file are merged. The built in merge tools only work on text files, but you can install custom ones. If there are conflicts, you must resolve them. If changes are not planned well, conflicts can become extremely difficult to resolve. Your knowledge of what kind of merges work well, and communication with team members, is critical. Remember git is a tool and it takes work. If used well it delivers a lot of value, if used poorly it can cause serious issues.

File Areas: Worktree, Index, and Repository

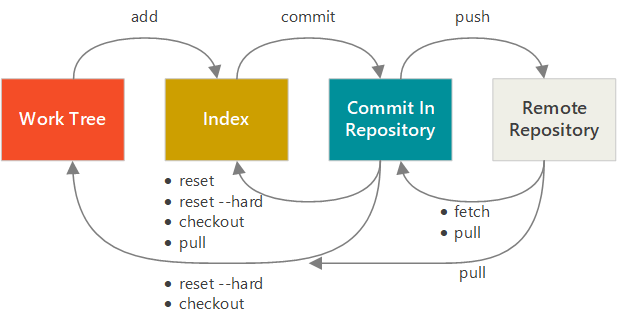

The commands add, commit, checkout, and reset copy files between the “working”, “staging”, and “repository” (i.e. commit object) areas.

Notice in this image how the “Work Tree” and “Index” areas are not the same as the “Commit In Repository” area. If files in your work tree have not been added and committed, they are called untracked and are not protected by git’s immutable data structure. Many commands modify the work tree and may remove files without warning. Leaving untracked files in your work tree is the most common way to lose work in git. If you’re not ready to commit a file, use the stash command to save it, or make a temporary commit and tag it to remind you of what you need it for.

The Index

The index is commonly misunderstood, and one of the big things almost every git GUI does not properly support.

The --patch option works with several commands like add. It lets you put only some of the changes you are working on within a single file to the index, so you can make commits without mixing up unrelated work. For example, if you are working on a large change in Main.xaml, but notice a small bug to fix, and you can add and commit only the small part of Main.xaml related to the bug separately before your large change is completed.

The --cached option works with several commands like rm. It lets you operate on the index in cases that by default operate on the work tree.

Commit Level vs File Level Operations

Reset Demystified is an article in the official Pro Git book that was key to my understanding of git references and essential commands. I recommend that you read it in full. I often reference the table at the end. It’s so good, I even copied it below with clarifications.

Read the next section in about Refs and Objects for a brief introduction to refs like HEAD and branches.

Moves HEAD or branch? | Copies to Index? | Copies to Work Dir? | Work Dir Safe? | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Commit Level | ||||

reset --soft <commit> | HEAD and branch | No | No | Yes |

reset <commit> | HEAD and branch | Yes | No | Yes |

reset --hard <commit> | HEAD and branch | Yes | Yes | No |

checkout <commit> | HEAD only | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| File Level | ||||

reset <commit> <paths> | Neither | Yes | No | Yes |

checkout <commit> <paths> | Neither | Yes | Yes | No |

Refs and Objects: HEAD, Branch, Commit, Tree, and Blob

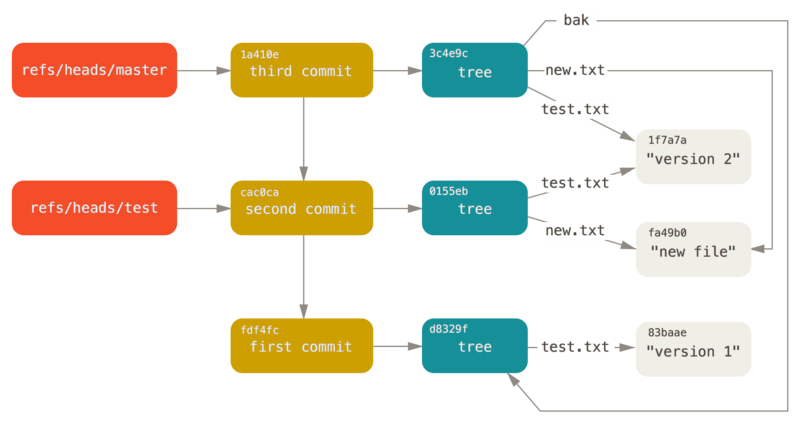

Refs are HEAD (not pictured), branches (orange), and tags. Objects are commits (yellow), trees (green), and blobs (gray). In a command they can be referred to by a ref that points at them, or their own specific hash number. Not pictured: HEAD points to a branch.

Data Structure

Internally, a git repository is just a bag of objects connected by pointers.

HEAD Points to a Branch

Many git commands let you omit what branch to operate on, defaulting to the branch HEAD points to.

Sometimes git can be in a “detached HEAD” state, where HEAD actually points directly to a commit hash instead of a branch. To fix this, just checkout a branch. Similarly, when resolving a merge conflict or editing during a rebase, HEAD does not point to the final branch until you have finished.

By default a repository has one Working Directory and one HEAD. Use Git Worktrees to checkout multiple branches at once, each with their own HEAD.

Branches are Just Pointers

Branches, tags, and other refs are simple pointers to a single commit, not like folders of commits.

Git doesn’t remember which branch a commit was made on, instead it is said that a commit is “reachable” from a branch by following the commit’s pointers to its parents. After merging, a commit is often “reachable” from multiple branches. The internal file in the .git folder that “stores” a branch only contains the hash of the commit it points to. That’s it!

In the image, “first commit” (hash fdf4fc) is reachable by both master and test branches.

Commits are Just Pointers with Metadata

Commits don’t contain the files themselves, only pointers to other commits, a pointer to a tree, and metadata like the author and message. The pointers between commits form a Merkle tree that you see when in the log graph when you use git log.

Trees are… You Guessed It, More Pointers

Finally, trees contain the pointers to the blobs that store the files. When there are files that remain unchanged over several commits git does not duplicate them, instead the new tree points to the same blob.

Trees are not often dealt with directly, so most users don’t think about them. However, ls-tree is a useful command you can use to view the folders and files in a commit without having to load it into a worktree with checkout. Try the following command to see only the folder structure of a specific commit in a repository. git ls-tree -r -d --name-only <branch>

Blobs

Blobs are the objects that store file content.

Commands like reset and checkout copy the content into the index or worktree depending on the form used.

Sometimes it is useful to view or retrieve only one file from a commit without having to overwrite your other file areas. The show command can be used with the branch:path syntax to specify the blob. To quickly view a text file in “Git Bash”, pipe the output of show to the less command: git show branch/name:path/to/file.txt | less Or, to output the content to a different file name, use a bash redirection operator: git show branch/name:path/to/file.txt > path/to/file-OtherBranchVersion.txt

Three Layers of Abstraction

Change

A commit is often conceptually described as a “change”. When we use git rebase, we talk about “applying” the changes to a different part of the repository. However this is only the first and highest layer of abstraction, and does not fully describe how git works.

Object

The image above shows the second layer of abstraction, where we can see that each commit stores all files in full size.

At first this seems inefficient. But there is space savings due to git’s design as a “content addressable” system where files that do not have changes have the same hash code, so multiple trees can safely point to the same file.

Pack

Finally, objects are only temporarily actually stored in full size. In the third and lowest level of abstraction, git moves older objects into Packfiles where they are efficiently stored using delta compression.

Tip: Commit Small Changes

Immutability Gives You Safety to Make Changes

All objects are “immutable”. They are never changed, git only creates new objects. Objects are not deleted during normal operations, only during garbage collection. For objects to be deleted, they must be (by default) 2 weeks old and not reachable from any ref or reflog entry (which expire when they are 30 days old).

When a commit becomes unreachable from any branches, thus disappearing from your log graph, it still exists. One command you can use to find lost commits is reflog.

For example:

- You’re working on

masterand commit your latest work with:git commit -m "My brand new feature."Your log graph shows:

* 4d2476f (master) My brand new feature.

* 6fe53e1 Work in progress.

* 2486da5 Work in progress.

* 496d993 Create repository.

- You change your mind about something, and want to fix it so you run

git reset --hard HEAD~to undo the commit. Oops! You shouldn’t have used the--hardflag, you really wanted the changes to stay in your working tree so you could edit them and commit again, but now your working tree has only the old files from before your change. In your log graph, it looks like you lost your work:

* 6fe53e1 (master) Work in progress.

* 2486da5 Work in progress.

* 496d993 Create repository.

- To get it back, you can look at the output of

git reflog master:

6fe53e1 (master) master@{0}: branch: Reset to 6fe53e1

4d2476f master@{1}: commit: My brand new feature.

6fe53e1 master@{2}: commit: Work in progress.

2486da5 master@{3}: commit: Work in progress.

2486da5 master@{4}: branch: Created from HEAD

- To keep this example short, we’ll simply add a branch there again. You can use the abbreviated hash:

git branch recoveredWork 4d2476fOr use the RefLog Shortnames syntax:git branch recoveredWork master@{1}The graph now shows both branches.

* 4d2476f (recoveredWork) My brand new feature.

* 6fe53e1 (master) Work in progress.

* 2486da5 Work in progress.

* 496d993 Create repository.

The reflog records entries of every type of action including merge, rebase, reset, and branch -f (force a branch to move).

Don’t be afraid to try something, it’s easy to go back if it doesn’t work out.

Tip: Immutability Gives You Safety But Don’t Make These Mistakes

Read More

You can read more in the Git Internals chapter of the Pro Git book.